The Innisfree Poetry Journal www.innisfreepoetry.org by

A CLOSER LOOK: Rod Jellema

Each poem that survives its own process of being made beckons you back for a few minutes for another look. If it looks unlike what you're accustomed to—good, that's the point. You don't have to analyze it; just let it do its work. And its work is to make experience in some fresh and direct way rather than to exult over it or chat about it or explain it.

. . . .

This making of poems is really not such a goofy or precious or starry-eyed thing to do. . . . We all recognize some creative longings and stirrings in ourselves: that fading Polaroid snapshot of the old Latin teacher, or the postcard you wrote from Viet Nam, don't quite do or say what you want them to. There are auras of implication you didn't explore. You see such implications sometimes in the swaying of an ice-covered branch, in a mysterious movement of words and their sounds through certain phrases, in a strange awareness that can move us when we remember a lost schoolmate or hear breaking waves in the distance.

Preface to a closer look at the poems of Rod Jellema:

I keep watching hoping I am reading the right signs. —Rod Jellema

A

fairly rare thing among us, a Frisian-American poet, Rod Jellema gives us poems

so full of music and memory, time and pleasure, faith and humor, that we are

drawn back for repeated reading and experiencing. And his life's passage

in art is as compelling as his poems: As he recounts in a 1993 interview

with Christina Daub for The Plum Review,

he taught poetry and creative writing at the University of Maryland before finally

beginning, in his forties, to write his own poems.

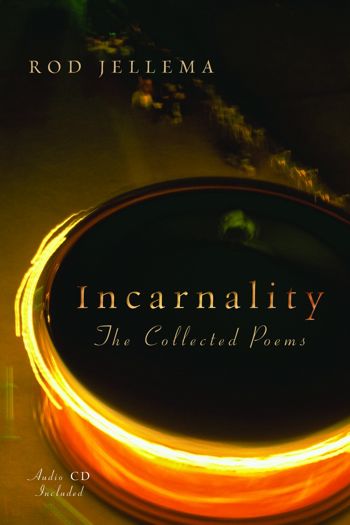

The prose passages above, taken from his introduction to his recent and wonderful, summative book, Incarnality: The Collected Poems (Eerdmans, 2010) (http://tinyurl.com/46lwfrv), reveal the mind and heart of the teacher who sought not so much to impart or instruct as to share in finding, as he himself was finding, the footing that permits the leaps of language required by poetry. Language, he thinks, is for poets much more than a tool—it is a self-generating source. Words—not ideas or techniques—words are the stuff of this art, not its brush but its paint. For many years, Jellema taught at the University of Maryland

and at The Writer's Center in Bethesda, Maryland. His first three books

of poems, Something Tugging the Line

(1974), The Lost Faces (1979),

and The Eighth Day: New and Selected Poems (1984), were published by Dryad Press. His translations of

Frisian poems, Country Fair: Poems from Friesland since 1945 (1985) and The Sound that Remains: A Historical

Collection of Frisian Poetry (1990), were

published by the William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, as were his two most

recent collections of poems, A Slender Grace (2004) (Towson University Prize for Literature) and his recently published collected poems, Incarnality

(2010).

Along with this closer look at Rod Jellema's work, Innisfree is pleased to publish in this issue an insightful review of Incarnality by the Israeli poet Moshe Dor. In addition, here are the comments of two major poets on earlier collections of Jellema's poems:

On A Slender Grace:

"Rod Jellema, like most mystics, starts small and ends

large. . . . He looks at a green bean and sees 'the holy scent of turned earth/slendered into a bean.' But he is a mystic who never becomes mystical; he never loses touch with the earth. He is a poet of deep and humane good sense who's infused with an abiding awareness of the holy. There is much more than a slender grace in A Slender Grace." — Andrew Hudgins

On The Lost Faces:

"What is new and comparatively rare in poets is his discovery that a lyrical impulse and a meditative urgency may alternate, feed off each other, disguise themselves as each other. . . . Supple technique accommodates process. . . . [The poems] show a technique forged from confrontation with the demands of content to become formal. That is what good poets can do and less good poets can never arrange." — William Matthews

Let

the Eyes Adjust Selections from Rod Jellema's Collected Poems

Aphrodite at Paphos, 1994

When I saw her gliding naked through the surf divine body of perfect glistening flesh I snapped up my binoculars and they blinded me normal again.

The Goat Trade

Etched now in the nation's memory will be the picture of the stunned president . . . reading to school children from a book called My Pet Goat.

The Washington Post

In our part of the planet we don't eat the meat or look much into the yellow eyes of goats, so we never really took to the nightmare stories

of evil power, goat's blood, or satanic dances. The half-man-half-goat piper is all Greek to us, could as well be from the other side of the moon.

Even the oversexed smelly old guy who reminds us of the buck in rut seems borrowed from a world of veils and tents.

Our own goats, now: they dance and sing, they kneel on their knee-bones in meadows under stars, they climb wire fences and carouse their way through little colored books we read to our children.

As for goat marketing, we're good at that. The ancients tanned the goatskins to make wine sacks and parchment, and goat hairs made fine little brushes for artists.

When they needed more than art to hold the mind to what's beyond the flesh, monks would cut from goats their hair shirts, rough and scratchy.

Since then we've raised the goat trade to match the higher standards of our way of life. Women shop for kid leather purses and gloves and the softness of cashmere or angora stoles;

the yachtsman takes a touch of distinction from sporting a goatee. And though eating goat is still rare among us, we often permit our delicate palates a small wedge of imported chèvre cheese.

Still. What is that lone black silhouette, with beard and broken horn and bundle on its back, that we see in flashes or dreams, feeling its way blind as it escapes along the burning sands?*

*Surfacing sometimes from deep inside the Judeo-Christian mythos is the wandering goat. The ancient Hebrew high priest, on the annual Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), would place upon the "scapegoat" all the sins of the nation and release it into the wilderness, bearing "all their iniquities unto a land not inhabited" (Leviticus 16).

The Potato Eaters

Vincent Van Gogh, 1885

Something looks wrong. Five peasants sit askew to the four-square table which slides away in reverse perspective into the darkness. The lamplight holds them still, their skins like potatoes, gnarls and knobs of brown hands reaching into the dish of white flesh. What rises from the dish like a prayer is not a transcendent breath of light — it's only steam off earthy potatoes. The figure who breathes it in is only a girl, and she gives us only her back, which is wingless and dark and blocks our seeing, or ever partaking. As the walls close in, they sup without communion, avoiding each other's eyes. The instability calls us. We lean so close we might fall into their ritual, unwelcome.

But the dark lets us in. These potato- people cracked by sun and wind and dust are created from the dirt dug daily with their hands. What shines their supper of potatoes to life and dignity is not artistic arrangement, expressive eyes, not the painter's spirit brushed piously in— for Van Gogh it's sacred skin the color of dusty potatoes sanctified by its resonance with blue shadow green soap and copper alive in all that darkness. From threads he knew far down in the work of peasant weavers in Brabant, he raised from black as from death colors that bless — now it's burnt sienna, too, vermillion, ripe grain and violet seared in the soiled work-clothes and walls in which we learn to rest and make our peace.

Fishing

Up Words in Norway*

Why you ask would I try to lure a new poem by reading classified ads from a village paper in a country and a language I don't know? Well, first, it was late at night, and windy. Then too, an ancient wall clock was clicking out the seconds through the empty bar room of the old Norse inn near Haga, and almost no lights through branches from the huddle of houses. That's all good prose, but how test a poem that wants to come in?

Make it stay out in the wind and ring the bell a while as you start with what's not yet there. The first move is on paper. Sometimes, as on that night you ask about, I like to knock on meaningless foreign words, straining to hear strange sounds inside their shells. Villagers buying and selling engangs-varer — I'd guess that's Norsk for "outgoing wares," disposables — can start it off. Country voices break yard-long vowels on rocky consonants

— a child's bike (jente sykkel) or a fishing rod (fiskestang), cries out toward cast-offs — a svaer klokke (surely a large heavy bell) or gammel skjorten (perhaps old shirts?) — glorious junk coming to life as loudly or softly as my hunches for meanings will permit, sounds that almost touch now and then the pressures they hold that could make them sing. This might be when I know I've beckoned in from the windy porch a sprite of a poem to sit and talk as together we find it a body.*

*I have never been to Norway. I hope this strengthens the point of the poem.

Letter to Lewis Smedes about God's Presence

Dear Lew,

I have to look in cracks and crevices. Don't tell me how God's mercy is as wide as the ocean, as deep as the sea. I already believe it, but that infinite prospect gets farther away the more we mouth it. I thank you for lamenting His absences — from marriages going mad, from the deaths of your son and mine, from the inescapable terrors of history: Treblinka. Viet Nam. September Eleven. It's hard to celebrate His invisible Presence in the sacrament while seeing His visible absence from the world.

This must be why mystics and poets record the slender incursions of splintered light, echoes, fragments, odd words and phrases like flashes through darkened hallways. These stabs remind me that the proud and portly old church is really only that cut green slip grafted into a tiny nick that merciful God Himself slit into the stem of His chosen Judah. The thin and tenuous thread we hang by, so astonishing, is the metaphor I need at the shoreline of all those immeasurable oceans of love.

Adapted from an e-mail discussion, summer 2002

From Seaman Davey Owens' Diary, 1511

Merchant Ship Rhiannon 12th May Still bearing southwestward

The sea wide and endless under the creak of the boards that pull our twisting wake through tepid waves, with burning skin we are hurled day after day into and out of the stare of the empty sky.

Cut loose, we follow stars through black that curve us toward nowhere we know. Below deck we wrestle with damp gray sleep while the Captain whispers mad to the moon, they say, over charts the Padre says came right from the Devil.

Back in Carmarthen, same moon, neighbors rise now to cut and plane and square straight beams and planks for Jenkins' mill, and Gwynn joins the maids upstream to pick orange flowers, yellows, and reds, to plait in their hair.

Report from Near the End of Time and Matter

If only we could see for a moment the holy light we pursue. . . . Plotinus

Say it is now the third month of light. Your eyes can't filter it out. Try to tuck your head under your blazing arm, try to find the sloping back to shade. Out along the flat plane of your gaze no aura from tree can print itself on your eye. Remember colors? Thick and cool. Old saints in glassy rag and skin who hung between us and the Sunday sun. But now nothing shines in this total bright. There is no shadow flickering in a window, no dark in which to remember depth. Even the blood shade of your eyelid is clearing to white.

Meditation on Coming Out of

a Matinee I try to trust the light before I step off into it. I think death is not dark, I know my fear of the light. Death is more light than I can think.

I've seen what death feels like: I woke one morning to light from beyond the white curtain but the lamps in the room still on bright as if it's already night.

Yes, like that.

In the Dark

Drop to the dark, the deep cool and quiet, where insight catches what a child or a blind prophet sees, dreamed from behind the eyes.

Drift now, and imagine, here in the dark, in the black that was here before time was, uninterrupted by glare of all colors locked within it, drift.

If you kneel at Our Lady of Perpetual Darkness, you won't see the black light of candles lit by grief — or by wonder — except under tightly shut lids. Close the eyes. Now feel the touch

of a soft black wind that reminds you: darkness is the darkest of rivers, flowing underneath the earth, breathing under skyscrapers, cornets, under our shoes,

swelling in waves along the arteries to every idea or song ever made. Now in the dark, dream from behind your eyes. Deep below the undertow of minor chords, inside every heartbeat, feel the darkness moving.

Commissioned by the Capitol Hill Choral Society of Washington, D.C., read over Larry Eanets' piano performance of Bix Beiderbecke's In the Dark

from Dark Glass: Four Poems

(1) Breath

Bath Abbey, England, 1509

It's Thomas I'm called, sir, and as you see by the scorched apron, glassmaker by trade. In truth how we learned glassblowing is only by what comes down through the holy stories you know. We make glass from inside us, y'might say, by easy breathing of creator-breath or "spiritus" some call it. We breathe windows to life out of small rivers of steaming color by stirring impurities into the light — the alchemists' powders of iron, cobalt, copper — all earth-stuff, that's what pure glass lacks, dirt as dead as the dust Adam came from.

'Zounds, sir, what's it all for? Something o' this: when folk come inside it's from the west door they come, so it's dark, dark like a cave, like a womb, it's the womb of Our Lady. The windows pull folk into dreams, say the priests, to dream the whole Book from right where they stand, dream of God creating the world from black, dream Jacob and the angel, Our Lord and the Saints. Dream is what master painter tells us to make in glass.

So the colors we blow, score, and bind, it's said they make what's holy become real and right here — the wild spears of sunlight they catch from the sky — catch the same way, you see, as how the dust could catch and keep God's breath when He made our father Adam, catch the same way the Eucharist grabs and holds onto the Spirit whelming inside the reds and purples of

swollen grapes.

(2) Catching Light

Shelley's flight into abstractions, pursuing his shining Spirit far past all time and earth, blinded him to think that life itself like a dome of many-colored glass, stains the white radiance of eternity. But look: just stand in a dim cathedral, holding your gaze as tourist cameras click around you, and see how the colors give to the light streaming in from out there not stain but the very bodies for light to live in — see how colors catch the rays and hold them, free them from the homelessness of light's infinite journey as it arcs and speeds otherwise eternally to nowhere. Color lets light rest and simply be.

A Note to the Swedish Mystic Who, Writing about Laundry in the Wind, Says "The Wash Is Nothing but Wash"

It's here again — that late afternoon wind off the lake. It rises up and offers incense of lifted hot grape leaves infusing a laundry-like steam of wet towels and swimsuits tossed on the vine to dry. Above, two herons, buffeted toward inland horizons,

and now she is walking up the two-track road from the mailbox, slowly, reading a letter. Once again I know what's holy is not wind, it is leaves and wet clothes, words on paper, waves breaking off their sentences, her hair blown across her mouth, her own way of walking. The wind, Tommy Olofsson, is nothing but wind.

Civilization

Archaeologists in China have found the world's oldest playable musical instrument — a 9,000-year-old flute carved from the wing bone of a crane.

Los Angeles Times

Long before Greeks measured to mark the frets on their lutes, dividing tight strings by exactness of tones, long before that,

someone in China, probably a girl with time and some need to walk alone near the sea, lifted to lips the hollow wing bone of a crane

and blew through it, no thought of why, mixing sky-air that lifts wings and sleeves with the unseen source of life they called breath.

Imagine the whistles and arcing bird-cries these people learned to make as they breathed through bones with scaled apertures and lengths

and drilled little holes where fingers could find the tunes beyond birdsong they began composing. How plaintive and lonely the wordless sounds

must have been as they called out thin, rose, then drifted into and through the Bo leaves, over rocks, or hung like clouds of smoke in rafters, then

vanished as softly as morning mist off the Yangtze, thoughts half-remembered. But the tunes lacked grounding, lacked sounds that tied light melodies

down to stone floor and soil and the warm flesh of hands. Centuries later, long miles westward, high up in Greece and getting out of the wind,

chapped hands of shepherds and goatherds tugged animal guts and dried them and learned to snap their lengths of string to vibrate them

against flat wood, later hollowed out, to resonate the deeper tones for love or despair that Athenian throats would sing if only they could.

The sweaty pluck and thrum of finger and hand hefted earth sounds upward, rising to meet the vibrato of long breaths ringing out of

that hollow wing-bone, and the melding created dialogue, Greek harmony, music, compassion, a transcendence of selves, a republic.

Afterword: Fascination

by Rod Jellema

Think of poetry as fishing. What really pulls is the fascination of touching a deep, unseen world with monofilament line. It's wonderfully dark down there, so I can't see what might be coming along that I can possibly hook and bring up.

For me that's the creative process, the best way a poem of mine starts. I admit I waver sometimes in that old tension between making big affirmations or making creative discoveries. Occasionally I cheat a little and compromise. But I remind myself that pronouncing and teaching, even done cleverly or memorably, can best be done in sturdy prose; there's a more exciting kind of language for catching.

Poems show us we can now and then move past or over or under the rhetorical and systematic language of the intellect, the kind we "understand." Standardized speech, while it conducts our routine business, holds us in bondage. The nosy intellect likes to rise to its feet like a stern old Auntie, demanding no-nonsense "understanding." But that fences the poem in, cripples the power of its language, reduces the poem to making what the intellect can understand. And what it can understand isn't much. That's why we have arts.

Once a poem shoots over your Auntie's back hedge and runs, it can unleash sound patterns, metrical pulses and variations, dream-logic, psychological associations, sense experience, breaks in voice, undertones, overtones, juxtapositions. When I write I notice such things coming in. I am embodying what I cannot quite understand. I have to hope the reader, not demanding a prose "meaning," lets them happen. That's a lot of the fascination for each of us.

Because words are sources, energies, the big idea for a poem doesn't have to be there at the start. As words flow and collide and generate more words, they carry me into what I don't quite know but increasingly want to catch. It's play, really, fascinating play, playing out the possibilities of words, playing out line to a fish. It happens not so much in the mind by itself. It's playing that happens on sheets of paper or on a computer screen.

I once imagined on paper Adam—the Hebrew word for Mankind—a very human Adam who had made the first words, and now I catch him at play, fascinated, shaping out of the stream of words

his praise and wonder, the pictures in his head, sounds that would speak his loneliness, a few lines that might stay.

Copyright 2006-2012 by Cook Communication |