The Innisfree Poetry Journal www.innisfreepoetry.org by A CLOSER LOOK: Dan Masterson

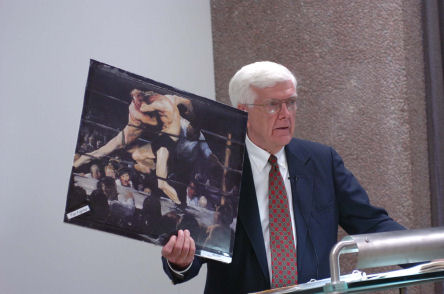

A recipient of The SUNY Chancellor's Award for Excellence in Teaching, Dan Masterson has directed the Poetry program at Rockland Community College for 45 years. During eighteen of those years, he also served as an adjunct full professor at Westchester County's Manhattanville College, directing the poetry and screenwriting programs, and continues his affiliation with that institution through a graduate poetry writing course he offers online. Upon his retirement from Manhattanville, the College's Board of Trustees established The Dan Masterson Prize in Screenwriting. He has just been named the first Poet Laureate of Rockland County, New York, for the years 2009 and 2010. Dan's fourth collection, his New and Selected, All Things, Seen and Unseen, was released by The University of Arkansas Press in 1997. His work has appeared in Poetry, Hotel Amerika, Esquire, Shenandoah, The New Yorker, Ploughshares, Poetry Northwest, Prairie Schooner, Artful Dodge, Ekphrasis, Poems Niederngasse, Chautauqua Literary Journal, London Magazine, OnEarth, Innisfree, New York Quarterly, Eratio, Mudlark, Poetry Kite, as well as The Ontario, Sewanee, Paris, Southern, Hudson, Yale, Gettysburg, Massachusetts, New Orleans, and Georgia Reviews. Additional information about Dan and his writing is provided in the bio space at the end of this feature. This Closer Look at Dan Masterson consists of two parts: first, a collection of six poems entitled "Sticks & Fists & Rosaries," three of which are ekphrastic poems based on the paintings shown, and second, an autobiographical piece, also entitled "Sticks & Fists & Rosaries," in which Dan reflects on the origins of these wonderfully evocative poems from deep in his childhood years. I. STICKS & FISTS & ROSARIES

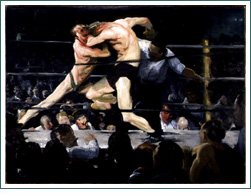

FIST FIGHTER

Saloon-keeper Tom Sharkey, retired heavyweight contender, is doing some fancy footwork in avoiding the current NYC ban on boxing by awarding 'membership' to every fighter he books for his Athletic Club brawls in his Lincoln Square cellar.

—The New York Times, 1909 The kid comes down Sharkey's stairs slapping Snow off his great-coat, the threadbare elbows Sporting ragtag patches cut from the hem. He's got a fresh shiner from one of the 3 other Smokers he's already worked tonight & a few Random welts starting to fade. He weaves his way Through the crowd, nods to Sharkey, unlocks The Stay Out door, & flicks the wall switch Before closing the door behind him. He hangs His coat on a hook near the speed bag, & turns It into a blur with a flurry of lefts & rights. He Steps out of his trousers, reties his trunks & slips A fold of 1's into an envelope: 15 of them, 5 bucks a win. He sticks it under the mattress He falls down on & closes his eyes for no more Than a 10-count. Up on his feet, peeling off His tee shirt sopped in sweat & spattered with Someone else's blood, he rubs his arms & yanks A clean tee shirt on as he leaves the only room Sharkey rents: half the kid's take per week. A dime for each piece of skinny-wood he burns In the potbelly. 2 dimes for a hot bath upstairs. Free beer if Sharkey goes out on the town. Sneaked Meals from the cook, Bernie, who calls the kid Champ and takes his break at 10 o'clock, in time To see the kid do his stuff. The main room’s filthy: 6 rows of metal chairs tight against a 9' x 9' ring Strung with braided clothesline covered in black Tape. 10 100-watt clear bulbs hang limp on their Bare wires, sawdust wet on the concrete floor, The potbelly's stovepipe jammed through the broken Glass of an overhead window nailed shut & painted Brown, an open drain in a far corner: Sharkey's "Please Flush" sign a ten-year-old bad joke, stale beer sticky Underfoot, cigar smoke & old men with nowhere To go. The kid's heading for the ring, lifting 2 rolls Of waxed-gauze from their pegs & 2 hollow stubs Of hose to support his closed fists. He wraps his hands As though they are already bleeding, round and round, Flexing his fingers as the knuckles grow padded and tight: The only gloves Sharkey allows. Just 18, the kid's in his 4th season, & his pale Irish grin, riding above thick shoulders, Is clean except for some hack doctor's stitch marks Under the left cheekbone. He climbs through the ropes & Sits on the stool, fondling his mouthpiece, & studies The empty stool across the ring, wondering who it will be, & now there's Harris stepping through the ropes, his Bare knuckles showing through the gauze: a leftover Wrap-job from his earlier fight down the block Somewhere. Getting too old for this stuff, 37, 38, Starting to lose his edge. It'll be okay, thinks The kid. He decked Harris in minute 6 last night At Ramsey's & he's got no defense left, just a pecking Jab & a giveaway right that opens him up for rib shots That put him down & a jelly belly to keep him down. Sharkey's playing ref again, calling them to the center Of the ring: No gouging, kneeing, biting, wrestling, butting, Hitting low, no clock. You want out, you stay down for 10. Go. from Ontario Review

GOING THE DISTANCE The late June sun had come in the window over his mother's bed, and he used it to make shadows on the wall, but they came out looking like ropes, tight twisted things, wrapped around themselves. He flicked all ten fingers and closed them into fists, pressing knuckles to knuckles until they hurt, as they did when he'd fight in the schoolyard. They were big hands, like Grandfather Fitz's he'd been told, the man long dead, whose sepia eyes never closed as they stared him down from the opposite corner, the oval portrait leaning too close on its wire. He knew he shouldn't look below the frame at his sleeping mother, but he did, sometimes, and saw things. He did not enjoy seeing her nightgown hiked up to her hips when the sheet slipped away in the night. He wished he could yank it down, tuck it in, pin it tight to the binding running around the mattress. What he liked best was lying at first light, her long braid brown and inviting, almost touching the floor. But he grew afraid when once she half-roused and turned, a shoulder strap slack enough to reveal a breast, the only one he'd ever seen. He tried to remember nursing at it, wondering if he'd fondled the braid as he fed, if she caressed him in his nakedness. But then he'd shut his eyes and turn to the wall, getting his face as close to it as he could, his left hand strained and flat against the cool blue plaster. Often, near morning, she would say things in dream, and he would cover his ears and hum until he heard nothing at all. And now, on this the last day he'd ever have to spend in grammar school, he lay awake in the room he'd always shared with her, and thought about His father far down the hall in his chamber, his bothersome snoring muffled from Mother's delicate sleep; his sister close on the other side of the wall, in the room he wanted for himself. He shut off the alarm Before it clanged and was relieved to find his mother wrapped, tangled, only a big toe jutting out for air in the narrow space between them. Downstairs, he smeared a piece of bread with apple butter and sat on the porch, remembering the summer morning his sister forced him to stay on the bottom step while she repeated the lie of a woman in a long black car who would soon be at the curb; she would wear a black dress and gloves and laced boots. She would take him away. He licked the last of the apple butter from his thumb and went off the back way, over the fence and down the path; he was late and stopped to get a scolding note from Sister Helena. When the last of all bells rang for the day, he opened his locker and stuck his copy of Ring magazine in his back pocket and took the leftover bottle of ink to smash against the brick wall rising high over the rectory window, someone yelling, promising there'd be hell to pay, calling him by name but in a voice that knew it was best to leave him alone. At the end of the block, he settled under a tree, the largest maple on the Town Hall lawn; he thought of it as his own and came to it on such days. He pulled his magazine out and uncurled it, Billy Conn on the cover, his cut-man taking the stool out of the corner, the ropes tight behind him, thick and twisted, wrapped in tape. The idea hit him like a quick jab: he could have a ring! The hardware store had clothesline. He slipped one inside his jacket and paid for the other two. And then home. No one was there, and he went to the cellar. He undid the clotheslines and looped the three ends around the first steel pole that supported the main beams of the house. And then the braiding: crossing the strands, as he'd seen his mother do a thousand times at her vanity, stopping to straighten the snarls, to tighten the loops; inch by inch it grew from pole to pole: the top rope of his own ring, his own place, the rope burns on his hands reminding him of the shadows on their wall this morning, Grandfather's eyes, his mother's long plaited hair half undone by sleep. He wouldn't use tape; he wanted the strands as they were. The last knot tied, he slapped the rope and it almost sang back. He went to a neutral corner and saw Billy Conn coming at him. He circled to his left and kept away till the round was over. He stepped out of the ring and did some shadowboxing near the washtubs, banging away at the air, talking himself into a frenzy, taking a few shots to the head, the gut, moving away, jabbing, sticking, until he was soaking wet. The faucet squeaked when he turned it on full force, cold water drowning out everything, hands splashing it everywhere, his shirt and slacks and undershorts peeled off, a bath towel stiff but dry hanging from its nail near the stairs. Barefoot and naked, he stepped back under the rope to dry off in the ring, wrapping the towel tight at the waist, tucking it in, arms held overhead in victory. And then the army cot, folded within reach, to be snapped open and snugged up against the pole closest to the furnace, two full floors beneath Mother's bed. He stretched out on the taut canvas, his left arm across his face, the right finding the braided rope, curling his fingers around it, tightening his grip, running it slowly out and back as far as he could, his mouth going dry as he felt the strands rise and disappear in the palm of his hand. from Those Who Trespass

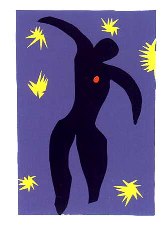

TUNNEL OF CLOISTERED REFUGE

Once again, reports have surfaced of a holy woman sequestered in the city's subterranean world of storm drains and tunnels. The location of her heavily guarded sanctum, a haven for hundreds of homeless, is unknown to authorities who debunk her existence. —The Underground Weekly, 1999 Mother Shulamite, her ashen hair In shroud, dismisses the threats, But those she tends make sure She's never alone. They are The throwaways found in alleys, Bent against crack-vents & curled Atop gratings: the Croakers, the Grunts, the Crattles, Geezers & Floppers, dozens of Loogans, Bawdies & Scavengers tucked in With Tipplers & Hooligans, Snarlers & Bumpers, a flail of a Rager here, A Defrockee there, a Prophet who Once straddled the curbs for bands Of minstrels stomping their muddy Time for the only Elegante tapping His wooden way on a dog-headed Cane. All finding themselves here Thanks to her main runners led by Yves & Catherine & Fournet who Brought them to this baggage tunnel Long dead beneath Park & 72nd. Brought here for their greatest Comfort, bundled up for safekeeping Far below blizzards overhead, Together in awe of the woman who Raises her hands in a hint of blessing, Enthroned in a lanterned perch of Steel fencing strung flush with sponge Rubber slabs, the high-back Cathedra, Its armrest removed to make way for Bench slats & struts & hinged relies Cut into blocks & screwed to stump Wood to receive & support her Sprawling weight beneath layers of Burlap robes gathered & draped & sewn to Enhance the dignity she wears as lithely as A princess at a garden party, but the only Gardens here grow limestone rosettes Arranged by seepage bubbling up along The jagged curves of decaying walls Enclosing the shallow platform where She sits over damp ground kept warm by The steam pipes that do their hissing only Inches away, while she intones her prayers Of her waking hours for those in her care, Fondling the rubbed & knobby beads she Reveres, carved from knuckles of nuns long Dead in the convent of Lost Emilia. This Evening she has the company of those most In need, who watch as she watches over Them, her lips forming the prayers they Feel healing their sores, bringing them Back from the frigid gutters of their Dreams. Thirty in all, laid out before her, The canvas slings of their pallets propped Above the wet floor, layered with plastic Sheets wrapped with newspaper batting: a Warmth unknown on the streets overhead. She rises & descends the ramp to the Suffering, allowing the beads of her rosary To drift across each body, her own hands Emitting light as soft & blue as that seen in A child's eye, leaving a halo hovering In place above the brow of those touched, A sound like muted litany flowing from their Throats in praise of the woman moving About them, her fingers magnified to Splendor, knuckles inexplicably flayed Sculpting themselves into rosary beads left Unstrung, the gasp of prayers as quiet & Holy as bone. from Georgia Review

THOSE WHO TRESPASS He'd find them among fallen limbs and brush in the pitiful stretch of trees they call their woods: stones the size of grapefruits, lugged out to the driveway to be washed off with the garden hose and left to bake on the blacktop in the high sun before being tucked away in the trunk of the car, along the sides, some down in the well, snug against the spare held fast by the stretch-strap doubling as the tire-iron brace, a four-pronged plus sign looking more like a silver cross the way it is propped, as though its Christ had fallen off, perhaps still there laid out among the stones. Headed for Buffalo, the outskirts, the homestead where there were no rocks to line the rose garden, houses no more than a car's width away from the next, the narrow concrete tilting toward Bannigan's front porch. And his parents would be there, pacing the sunporch, waiting for the visit to begin: five days of clutter and talk, sleeping bags and diapers, suitcases, books, hanging clothes, shopping bags; space enough in the guest room. And then the stones, last, always last: a few at a time; each placed ceremoniously along the rim of the rose garden that curled against the side of the garage to the back picket fence, turning left at the Broderson's shed and back toward the house. Father is dead; Mother is gone, and soon strangers will be moving in. But the stones are still there, years of stones. Last night he went off alone to do something about that. He took only the three-inch paintbrush saved from his father's workbench, one of a dozen washed after every use, never to be thrown away, clean in its plastic pouch, the snap still intact. Seven hours by train, a short walk to the Delaware bus, twenty minutes to the city line. He gets off a stop early and crosses the street to the hardware store; the name has changed, common as a tenpenny nail. He chooses a gallon of black enamel and feels the plank floor shudder beneath him as the vibrator-stand shakes the can to a blur on the counter. His mother's hands are shaking in her room, some 400 miles downstate; if she had lids on the cups she would spill less tea on her sweaters and robe. He may suggest it to the home. Now, at 10:30 in the morning, she is saying her first rosary of the day, the floor nurse leading her on, bead by bead, as the paint slaps against its lid only a block away from the altar rail where she knelt for half a lifetime. She doesn't know what she is doing; she is seventeen again: Springville, her brothers bringing her candies, Papa home on weekends from the railroad gang, her mother, rosary in hand at bedtime, and Kathleen sleeping with her own beads under her pillow, the same rosary she holds in her grape-veined hands this morning, a day's journey from where he stands waiting for his twenty-dollar bill to be broken. She is alone for the first time in weeks: the nurse has left to check on a noise in the hall, and Mother goes on inventing melodies and words to replace the orthodox prayers once her own. In her wheelchair, the canvas waistband tight as a saint's hairshirt, she feels the beads loose in her hand. She fingers them, their roundness, small as pebbles, smaller than the stones her son has gone to see again. She is drawn to the beads, sensing nourishment. Her lips are moving in prayers never heard before; her tongue is extended, her eyes closed. She bends closer to the beads, accepting them now like the host safe in her mouth, sliding slowly as forgiveness on the same saliva the aides dab away with tissues. But now, it serves her well: for the beads have slipped fully beyond the lips; they could be green peas all in a row tumbling from a spoon, beginning their descent. No pain. No outcry; she is deep in a tangled meditation; only the crucifix is left dangling against her chin, its small silver link holding fast to the first of its fifty-nine beads. Christ is in His diaper and the thorns are intact; He is swaying slightly swaying, His features rubbed away by Mother's mothering. They retrieve the rosary and dry it well enough for her to go on to the next decade, the connected beads back where they belong: in the tiny palm that waited like a cradle or a font or a crypt dark behind a large washed stone. The paint can is freed from its shaking. He takes the gallon as it is, swinging on its wire handle, and drops the change in his side pocket. The town seems almost the same: the village hall, the playground at the corner, Kay's Drugstore bought out and revamped from counter to name. The sun is hot as he turns down Lincoln Boulevard. The house is vacant; he decides not to use the spare key for any last look. The backyard is his grotto and he goes to it. The stones are still in their looped line skirting the edge of the rose garden. He stands frozen in place. He wants all of the stones; he wants to take them back to the ground he walks every evening, the frail run of trees that flanks his house. He feels for his rosary and finds it in his suitcoat pocket, kept there for good luck. He takes out the beads on barstools sometimes, to fondle them in the dim light, saying their prayers half in a trance, and in churches he needs to find when he is alone on the road, cities he doesn't want to see ever again. The stones must stay. And so he begins: within minutes they are laid out in a wide circle. Some of them tipping, a few already out of ranks, but each assigned a plot of ground: the paternosters, the aves, the tenth aves each doubling as a Gloria Patri. The shrubbery encircling the yard is thick enough to hide him from the neighbors. He stands at the back of the lawn, at the strand of beadstones which must stray from the others so that he might affix the crucifix-stone to its tip. He knew back home which stone it must be: the one with the purple vein running around its middle, and it is there. He loosens the lid of the gallon with the half dollar he brought from his dresser drawer, the chifforobe which once stood in his father's room and now holds his own socks and shirts and bonds and bills. The paint is rich, the brush still soft; he can smell the turpentine on the bristles, dry and stained deep with many colors far down in the base, each a different Saturday morning project done with his father on this property, before the stones, before almost anything. He kneels at the first stone and grabs too quickly, anxious to see the purple run of color, and jams his thumb, blood forming already beneath the nail. He replaces the stone and paints a rough cross on it, trying to leave the vein purple as a cinch for the stipe. He takes a giant step to where the next stone lies: the paint goes on with hardly a trace of dirt; another step and he is past The Lord's Prayer, onto the first trio of aves: the Hail Marys, one like the next. The black is as lush as the counterman said it would be. Another single bead, and he finds himself praying aloud, loud enough only for a stone to hear. Another space and then on to the flat slab of sandstone he knew he would use to connect the circle of decades. He gives it two brush strokes, unbroken, a child's attempt at the ancient fish, good enough for anyone who knows. Three spaces beyond the fish lies a speckled stone; it goes black, flush to the grass. Nine more go quickly, slopping the paint in a blob on top, all at once, scampering back and forth to smooth out the drippage, ripping away the blades of grass that are stained, stuffing them in his back pockets. He says the prayers as he paints his way through the next ten; one has a bit of moss from the shaded area along the spilloff spout on the garage roof, the others bare as the edge of grave markers. It takes three Hail Marys to paint a hail mary, the phrase "blessed art thou among women" the line that slows him down: he finds himself repeating it, remembering the pitchers of lemonade Mother would leave in the shade with chipped ice and a tall glass when he would use the handmower on a hot day. He is rubbing the grass now, the way he did when he was a boy, after cutting it twice, once fence to drive and, again, from garden to house. He would sit and sip from the sweating glass; the grass, the smell, the silent creatures he'd disturbed, all holier and cleaner than the wood trimming the stations of the cross in the church a block away over the back fence. He runs his hand across the grass until it hits his leg and wakes him to his task. Decade two. The stones are dusty and pitted. It all takes too long and he wonders if the weather will hold. He crawls on to The Lord's Prayer, three spaces away; he smiles as he comes to the words, "Those who trespass," and looks over his shoulder toward a space in the hedge, but knows that what he is doing is his to do. The third and fourth are almost too much. The paint needs stirring, the brush is filled with dirt; his time is running out. If he were to show anyone a decade, it would not be either of these. The paint is too thick, the grass too black, the stone-face showing through too often. He must finish and get away; he feels it in his wrists and ankles. He wonders if he should have come at all. His thumb, with its nail blood dried black, is numbing. He needs to be home, close to his own ring of stones at the far end of the property where he can sit and poke at the mild fires he builds there, feeding the flames with twigs and branches fallen on their own, the rocks large enough not to split from the heat, high enough to contain the blaze. But it is time for his best work. The paint goes on like cream, as thick as the cream that came in the bulb-topped bottles of the forties that the milkman would leave in the back hall during the war if they'd remember to prop the shirtcard cow in the window alongside the sign for the iceman and breadman, Smooth as the blade of grass he holds still between his lips, thin and slick, not a blade to crush between thumbs to make an unseemly noise, not one that would grow in a back lot, but one like all the others in this yard, planted by Father, tended by Father, watered by Father at dusk while other lawns went to seed and crabgrass and weed no one could name. It tastes good and clean and cool. And now it is done. The last bedrock black as the pieces of coal he was allowed to pitch into the yawning furnace, when Father would bank the fire, at nine-thirty every night, so that they could awaken in Lake Erie winters to heat rising from the floor grids. He looks back at the house, up at the window where the afternoon light is spreading its daily shadow across the corner of the small blue room he'd shared with his mother. He goes to his knees and puts the lid back on the empty can. He wipes the brush across the label, the brand name, the directions, the cautions, cleaning the bristles as best he can. He will finish the job as his father would have him do, but not here; back home, at his own bench in his own garage, where he belongs. He slips the brush into its plastic sleeve and drops it carefully into his inside suitcoat pocket and walks to the corner of the house where the same garbage cans wait hidden behind the spruce trees. He lowers the container far down inside the first and heads for the street; he does not look back. He has his wallet, his ticket home, his father's brush. He is listening to the angelus tolling from the parish belfry: six o'clock. But there is something else, quieter than the bells calling the villagers to prayer, something closer. It is his mother's voice, restored, the same voice that used to call to him from the kitchen window; she is obeying the ringing of the bells; she is intoning the beads he has left in her name beneath the Niagara sky: the threat of rain diminished, a healing breeze from the distant river drying the rocks where they lie. from Those Who Trespass

FENDER DRUMMING The unused lot behind the mall is lit Like noon by a circle of idling cars, Their high-beams isolating two Dusters, Dead center, parked grille to grille against Their owners' shadows tilted up to watch A coin disappear in a late August sky then Reappear, inside a broad band of light, flip Flopping to the gravelly dust that swirls Between their boots. Heads it is, And the one billed as Downtown spits On the dime for not being tails, rakes His fingers through his grey thick hair And takes his place at the right front fender Of the teenager's car, a fender left unwashed: A thud of curved steel waiting tight and thick And dull. He antes up His 50 bucks: blood money he rolls And sticks into the ridge crack, while Across the hood, the other they all call Kansas City kicks in his roll and peels away A chamois to reveal a hand-tooled fender, Its powder blue spilling over the edge Where his fingers are busy fondling it, Rubbing and stroking it, preparing it For all the things he has in mind. The others know the rules and leave Their cars, hushed, pressing the doors shut, To sit on their bumpers, leaning back, allowing Their engine blocks to shudder through them, Headlights free to do their job no more Than ten strides away from the drummers Already testing the metal: tapping and banging, Riffmg away, a run of triplets here, a ruffing There, half-drags, flams and paradiddles, Feeling each other out with low caliber shots Delivered at point-blank range. They stop and hold their hands up open For inspection, proving they have no boot Wax no epoxy no nu-skin no clear polish no Thread-tape no polyethylene, nothing But scars to keep their flesh from popping On impact. And then the once-only passing Of fingers behind the ears, across the brow, Picking up any oil they can find, forcing It deep into the finger pads they rub-up Aside their ears, hearing the friction Lessen as each skinprint starts to slicken. They nod and KC hits the slap-clock perched On the hood-drain, stepping back as Downtown Whirls his fist high overhead, slamming it Back down into the fender as though burying A knife up to its hilt, leaving a crater Round as a saucer and thrashes out his Opening burst against its rim: a signature Ostinato built to last: a flat-handed Ratamacue, its 4-stroke ruffs chasing The diddy-raks of lefts and rights, their Accents all in line, letting it flick Off into what sounds like a wrong turn But brings him to a dark side street where He plays mean, trashy shots slashing a foot High without blood, laying down blisters That ring true, smudging the crosstown Rumors that he was easy: nothing more Than a down and out ham-and-egger broken By endless weeks on the summer circuit. The alarm clangs and Kansas thumbs it back To Start, using the top arc in offbeat Only to sweep it aside with a triple Chop and the 12-count pause the crowd knows By name and chants across the gravel: Let The cat out, Let the cat out, Let the cat out, Now; and he's off, the fender swelling On its struts as he knocks its brains out, Whip-cracking licks coming from somewhere deep Inside; doubled over, his cheek touching The fender, he muffles some ruffstuff, his Thighs easing in tight, the tingle surging up Through his groin, his hands no more than blur As he lays down an intimate rumble, a morendo Delicate yet soaring from steel to paint to air, As the slap-clock takes his time away. Downtown sets the dial to 5 and takes A deeper breath than he should need, turning Toward his own car, tapping on the window For the door to be unlocked. He gets inside For who knows what behind all that tinted glass Rolled up tight against the local wannabes Who are running loose at halftime, banging Each other's fenders to beat the band, While Kansas City greets a curve of blackshirts That keeps the fans at bay, except for a sleek Young blonde who parts the crowd to drape a towel Loose over his shoulders before sliding her hands Down his arms in ritual: a kiss applied to the tip Of each finger as he slides them splayed open Across her lips, parted to allow her searching Tongue to apply its healing balm; KC stays put and shakes his hands, as if he's Just washed them in a stream, before enclosing Her face in them, drawing her close, spreading The towel over their heads to disappear Into a long hidden moment that is ruptured By crackling thunder clearing the air For three jagged strings of wet lightning That send her away with all the others Scrambling for their jalopies, the rat-a-tat, Rat-a-tat, tat-tat-tat of the first plips Of drizzle augmented by wiper blades slapping Away in broken unison around the rim. Time. And Downtown steps out bare-chested, Wrapping his tee shirt in knots around his head, The rack of his ribcage showing through As he faces off in the growing storm for The Give-and-Take. No clock. Set Ready Go, And Downtown batters off his Blind Pig stutter Step. KC hammers back a hand-butt pounding Version of The Stumble Bomb answered in kind By Downtown's own knuckle-knocking riff of Let Me In echoed by a flathand read of KC's Small-arms Fire: a frantic run of punishing Half-drags, flams and rolls that Downtown Duplicates as the skies pour it on, drawing KC's healer back to his side, shaking In a chill she can't define, as Downtown's Car door opens and a woman, too old for such Weather, steps out and joins him without taking Her eyes from his hands that are running Rudiments with KC, beat for beat: ruffs, rolls, Paras and flams, ratams and trips and drags, Ignoring the rivulets streaming candy apple red With every slash they lay down: the women Edging closer but trained to know their place As split pads widen on each side of the hood: Trigger fingers tearing wide open, stroke After stroke after stroke flapping with less Force against fenders dancing with thick Needle-rain that scrims their hands and enshrouds Their women who sense a final thunder. from Georgia Review

STICKS

Back-street bars such as those located on West Genesee, Mohawk, and Michigan, have given rise to a resurgence of interest in cool jazz. The trend has afforded the area a much-needed economic boost. —The Buffalo Courier Express, 1951 His folks buy the lie: he'll hit the books Over at his buddy's house, & grab supper There, catch the Friday night double-feature At the Royale, stop off at the malt shop, & Be home around midnight. He slides his sticks Up his sleeve & heads off past manicured lawns, Alongside the library, & hops on the Delaware Bus heading south through the projects. Where Division cuts cross town, he transfers To the rush-hour local & rides it to the end Of the line, reading chunks of a crushed copy Of King Lear that travels in his back pocket, & still has time to work his sticks through A few rudiments before the bus does its U-turn in the train yards. Just two blocks Beyond the freight house, he takes the alley They warned him about, & comes out on Perry, Smack in front of The Kitty Kat, its transom Sign rimmed with rust but still pulsing cool Blue neon through the eyes of a snarling cat. Inside, wishing he were black, he sees what He hoped to see: Big-Gate Clossen setting his Traps, his ride cymbal blazing in the klieg Light's glare. The place is filling up, still An hour or more before the opening set of five, & the kid asks if he can drum for mike checks, & gets a Yes instead of the door! He rattles Off his own double-8: smooth triplets sliding Into a roll that blurs out atop the closed high Hat. The sound man wants it again, & BG stops To listen, & tells the kid to hang around, that He can sit-in for him on an early set or two. The kid nods, & slides his sticks into his belt, Somehow making it to a booth without his heart Banging through his chest. He orders a beer, but Settles for the ginger ale they bring him in a mug. The trio starts early, whacking the room awake With Frenzy, & eases into Bird's version of Easy To Love, BG's shading so delicate, his brushes Must be tipped by strands of velvet, not wire. The kid figures if BG waves him up, he'll go easy On the bass pedal, chatter some with both hands On snare & tom. Just like back home, behind the Closed French doors: Max Roach on the turntable, Perdido set at 78, & geared down to 33 for study, & back up to 45, before going flat-out at 78, Beat-for-beat with the master, ending with his Signature tinka-tink on the crash cymbal's crest. The trio's back from break, & BG's calling to the Kid. He's on his feet, hearing what seems to be Applause mixing with the pounding in his head, & Someone yelling for him to blow the roof off! from Mudlark

II. STICKS & FISTS & ROSARIES

by Dan Masterson

It was about that time I started writing poetry and stashing it out of sight in an orangewood box under my bed. My days began with a different wake-up call from my dad, always in rhyme, and at noon, I'd jump the back fence from the schoolyard for lunch with my mother, and talk about the new word she'd chosen from the open dictionary lying on the kitchen table. Toward the end of the school year, I stayed after class and asked Sister Helena if she'd read one of my poems. She frowned, grumbled, and yanked it out of my hand. She said, "There's an error in the first stanza. Do you know what a stanza is?" I did. "Well, if you find it and correct it, I may read the next stanza." "No you won't," I said, "because I won't show it to you." I was stuck with her for the next two grades, and she hit kids, but not me. My dad wouldn't allow any touching of me or my sisters. It drove the nuns nuts. It was eleven years before I showed anyone another poem: Professor Whitney at Syracuse University. He told me I had a good chance of being a poet.

I started drumming, back in high school—first on car fenders with a buddy, and then on a beat-up set of drums I bought in downtown Buffalo. I taught myself to drum by listening to 78 RPMs on 33 and then 45 and then back up to 78. One night, I took three buses down to the Kitty Kat Klub, a black jazz bar in Buffalo, with my sticks, and talked my way into sitting in for the drummer. Pretty soon, word spread that I was okay, and I was playing in four or five bars weekends. My folks never found out; they thought I was hanging out with my buddies. When we'd have high school dances, the bands would let me sit-in and do a solo at intermission. When I went away to college, I played at the Cadillac Lounge on weekends after I'd drop my future wife, Janet, off seconds before curfew. I'd join Kenny Sparks who'd be in his 3rd or 4th set, playing piano and singing, working his way through college. I'd play brushes on a baby conga I'd made from a nailkeg—and bongos for Latin stuff. After college, it was back home to a dj job at "WBNY The Friendly Voice of Buffalo"—until I left for the Army. Well, that's where the "Sticks" & "Fists" poems came from. The "Rosary" poems started during the 2nd world war when my sisters and I would join my Mom and Dad, kneeling on the living room floor, where my dad would lead the rosary. One Friday night, I must have been in 5th grade maybe, my father turned to me and said: "Why don't you lead us in prayer this evening, Dan." It was like being punched in the chest. I didn't have his thunder in my voice, but I got through it. I've carried a drum key in my righthand jacket pocket and a rosary in my left, all these years. The rosary beads used to get tangled in a roll of dimes wrapped in electrical tape (brass knuckles that don't show), just in case. Our household was strict Catholic: Confession, Mass, Communion, Novenas, the whole works. And it stuck for a long time. The rosary still feels good in my fingers, and the prayers to my head. But much of the orthodoxy has vanished, the church-going, the rules, and the holier-than-thous. Monkhood is good. But what stuck, really stuck. I'm part priest. Would have been if I could have married Janet, but I would have lasted about two Sundays before I decked Father Bingo who would have wanted to run/ruin my life. But a lot of good stuff rubbed off. And the poems are fueled by it, in an oblique way—but it's there.

Copyright 2006-2012 by Cook Communication |